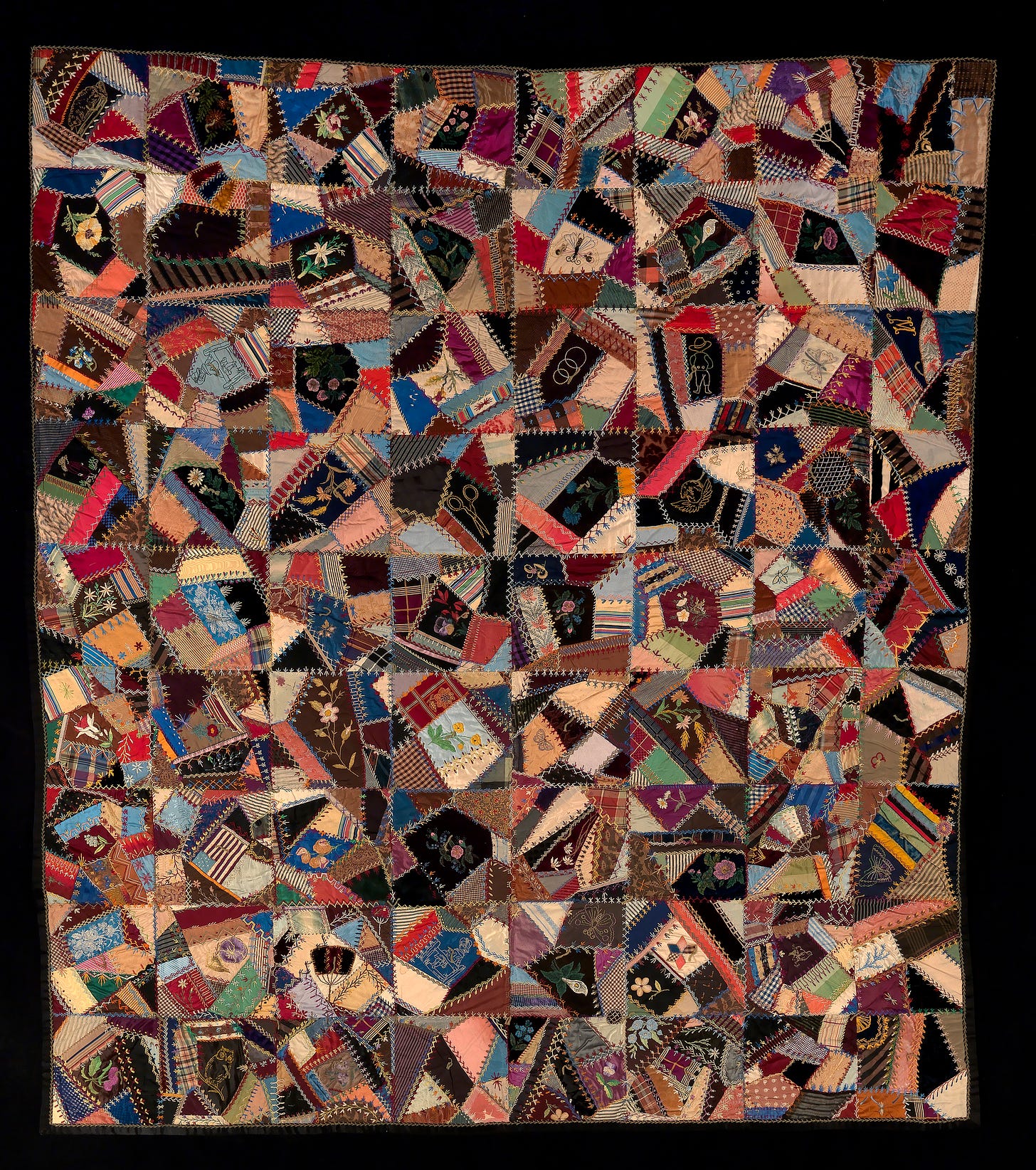

My grandma has a crazy quilt in her dining room that would always catch my eye during family dinners growing up. The patchwork style with exposed, embroidered seams dates back to the 19th century. The trend was deeply influenced by the industrialization of fabric production and globalized trade, resulting in access to a wider range of materials. Women confined to expressing their talents in the private sphere embraced decorating their homes with so-called “fancywork.”

In a history of the crazy quilt, American Quilt and Patchworking reported that “as random patchwork spread to both city and country folk, it became the first commercial needlework craze in America. By 1884, silk manufacturers sold kits of scrap silk. Cigar manufacturers wrapped silk ribbon around bundles of cigars, and cigarette paper manufacturers tucked silk premiums into their cigarette paper packages for men to give their wives. Women's literature supported the rage by publishing crazy patchwork patterns that could be ironed on, traced, or transferred to fabric.”

While crazy quilting may have gone out of style, patchwork has never lost its relevance in textile arts as both a practical solution when resources are limited and a creative process in and of itself: The V&A website has a nice summary of patchwork trends in fashion over the years. I’m particularly interested in how crafts that come about due to necessity become design trends and even considered art forms. (I’ve written about how World War II silk maps used by pilots were later transformed into chic garments during the period of post-conflict rationing.)

As the V&A writes, since the 1960s, patchwork has had a counterculture image, which resurfaced “in the early 1990s as part of the backlash against the slick corporate styles of the previous decade. Designers looked to create a handmade, homespun feel, as seen in the 'grunge' look promoted by Marc Jacobs at Perry Ellis. As street-style embraced a revival of hippie-style, high fashion designers watched closely.”

Today, patchwork is embraced by many sewists as a counter to textile overproduction and a way to practice zero waste. In my opinion, no one does patchwork patterns quite like UK-based ROBERTS | WOOD. While a sewist with some experience can hack a pattern to mix fabrics, ROBERTS | WOOD integrates a mosaic of materials into its designs. What I love most about the patterns is how intuitive they feel, and the endless possibilities for combining colors, textures and patterns.

When talking to other sewists about patchwork, they’re often intimidated by the sheer number of pieces involved and not getting lost in the sauce of the puzzle of making the final garment feel cohesive. My process usually involves finding a common color scheme in my impressive — for lack of a better word — fabric stash and a lot of trial and error. I also draw inspiration from other artists, most recently painter Auguste Herbin, whose Cubist works come across almost like modernist quilts. (Earlier this year, I saw a Paris exhibition dedicated to Herbin, who was rightly described as “the best-kept secret of the modern art adventure.”)

Herbin even created a language by combining colors and shapes in his later works, showcasing his true talent in taking abstractionism to the extremes. For this newsletter, I was so excited to chat with a more contemporary master of patchwork, Carly Bettinson, who’s garnered a large following for her impressive pieces. But first, some largely pattern-focused sewing world updates.

Scrap pile

Feeling spooky? Appropriately on the patchwork theme, the Prairie Misfit released a quilt witch hat just in time for Halloween. (I recommend the brand’s other very beginner-friendly designs.)

I’m also digging the new Cinch Me I’m Dreaming (great name) dress from Forest & Thread. On my to-make list is a similar channeled dress from Closet Core. The cinched trend seems great for a novice to take on, given the flexibility with sizing.

I had the pleasure of pattern testing the Faux Collar Oversized Button Down Shirt and Dress from Sewing Therapy. I made the cropped version with some funky vintage floral fabric from French brand Maeli. I’m excited to also make the cleverly pleated dress version.

It seems the fall patterns are coming in hot. Named Clothing just released its autumn line. The Loviisa Denim Dress has a very cute placket and pocket details. The new Juno Dress from Spaghetti Western patterns has a similar vibe.

A nice piece from Dazed on the rise of niche hobbies: “Brian Kochan, a 26-year-old yarn spinner in New Jersey, believes people are currently searching for tangible objects in general. ‘Many of us work an unsatisfying office job with few, if any, physical deliverables during a time when we are constantly advertised to overconsume,’ he says.”

I’ve had mixed results with magnetic seam guides that attach to sewing machines but Wirecutter is a big fan: “I’m not Cinderella, and I don’t have a bunch of very talented mice friends to help me out, but this tiny doodad is the next best thing.”

But on the Tiktok front, I’m so intrigued by the possibilities of a pinnable table:

And a classic sewing hack with a song!

Threading the needle with Carly Bettinson

Every edition of Sew You Have a Question features a Threading the needle interview with someone in the textile arts world who’s brain I want to pick. This time, I was so happy to chat with Australian sewist Carly Bettinson.

How did you start making your own clothes?

I was crocheting a lot in Covid time, and I started selling stuff in 2021, which is kind of crazy to reflect on. I was just trying to make enough money to fill in the gaps in my income because I was working as an actor. I don't know what was going on in my brain. But I was like, "Let's just see if someone wants to buy this." It kind of worked. Once it started heating up in in Australia and Brisbane for summer, I was like, "Oh, no one's gonna buy my stuff in summertime, so I have to learn how to sew." I don't know how that all made sense in my brain, but I just committed to it and fell in love with it.

Are you now sewing full time?

I'm doing sewing full time, but every now and then I'll do an audition. But it kind of feels like my Hannah Montana life. It's a bit off in the distance, I suppose, like an alter ego.

Do they feed each other in any way, those two very different art forms?

Probably. I love theater so much. I love costuming. At the risk of sounding egotistical, I feel like an artist who is just trying to find different mediums that I can express my creativity through. Sewing is one of them and singing is another. I'm sure there will be other other mediums throughout my lifetime that I feel excited by.

I talk to people who have been sewing for many years, and it's pretty amazing, all you've accomplished just in a couple. How did you build sewing skills so quickly?

I get a bit obsessed with things I'm really into: I spend all of my free time thinking about it. It's deeply fascinating to me, the way clothing is constructed. Once you rip the band-aid off and start exploring, you see there's more and more you can learn. It's like a treasure trove. I became fully obsessed with the craft, and I still am. But I'm also so happy to be making mistakes. It's not a problem to be bad at something and share it with the world. You're only going to get better if you keep learning. That's the ethos I went for.

What resources did you find useful while you were learning?

I watched probably every With Wendy video. YouTube is probably my greatest resource. Rosery Apparel and the Essentials Club are also amazing. In more recent times, patterns, having a dress form and just looking at the clothes I own and dissecting them have all been good. And textbooks as well. My favorite is Pattern Making for Fashion Design by Helen Joseph-Armstrong. Reader’s Digest Complete Guide to Sewing is cool if you want to look up a specific technique.

Was there something you know about sewing now that you wish you would’ve known when you started?

If I was going to be specific, I would tell myself to iron everything, pin everything, and that the bias, it's stretchy and on the diagonal. I think I had good broad concepts of what I wanted to achieve, but the specific skills, that's what I would say.

How did you develop your patchwork style?

Patchworking was kind of a means to an end for a little while because I didn't have any money to buy fabric, so I would thrift what I could. That often means you're not going to have a secured amount of fabric for a project. It’s so cool because historically, a big use of patchworking has been people being resourceful. Then I totally fell in love with the artistry of it, the fact that you can combine colors and prints in different shapes and combinations. It's endlessly fun and exciting, and it's so playful. It demands a response when you go out into the world, whether that be negative, intrigue or positive. People engage with patchworking in an interesting way. It makes them look. It's nice to have a conversation starter piece in your fabrication of what you've made. It's pretty special.

Patchwork might seem daunting going in. Can you talk me through your process, how it goes from a pile of scraps of fabric to a finished garment?

Oh, yeah, it is daunting. My fiance, Elijah, is an artist, a 2D animator. He's taught me a lot about how colors are friends with one another. He's broken it down in a friendly context like that. I use that terminology a lot when I'm patchworking. I put pieces of fabric together and ask, “Are they friends?” That can be really helpful so I don't get stuck on whether these colors go together technically, or whether you can put flowers next to vintage Daffy Duck fabric. It's kind of fun and goofy.

I've definitely grown a lot more aware of fabrication, whether they can be combined. But it's just been a lot of practice. That's another thing Elijah has said to me about animation, because you have so many frames in a second. Basically, he says that if it looks wrong, it's wrong. A big part of his job is figuring out why it’s wrong. Because it may not be extremely evident which frame is out of place. That sentiment has also made a big difference in terms of fabrication. If it's wrong, it's wrong, and sometimes you just put it on your body or you look at it and you're like, "Oh, those two fabrications are just not going to mix well.” I figure it out on the fly every time, or at least I try to.

You mentioned the importance of showing your mistakes. For how great the online sewing and crafting community is, the expectations of perfection can lead to false understandings of the work.

You're so right about that. It's so interesting because you'll look at a sewist's Instagram and think that is perfection. Then I'll read the caption, and it'll be like, "There's three things that are really wrong, and if I remake it, I'm gonna change seven different things." It's only because of other sewers' transparency of their process that I've been able to learn. With Wendy is an excellent example of someone who's always shown her whole process. Every time she makes a mistake, it's just information for me. I've learned so much more from people like that than people who just share the perfect end results. It's definitely really uncomfortable. When I share mistakes on YouTube, I feel like this must be boring and I don't really feel confident in its value. But it is informative.

How would you say your style as a designer has evolved?

It's colorful and playful. Technically it's a lot better sewing than at the beginning. I'm kind of embarrassed about my first year and a half of stuff that I sent out into the world. I wish I could do it better. But I think the core of my work is pretty similar. It's just about play and childhood and light. I want my pieces to feel fun. You're putting on something you would have loved to put on as a kid but an adult version.

Could talk through the process of a recent project?

I made a piece recently that I'm really proud of. It was for a charity called Dangerous Females. They raise awareness for those suffering from domestic violence in Australia. I had this idea. I wanted to see how effectively I could patchwork an ombre textile. I drew my sketch and cut out these really skinny strips of material about two inches wide, hundreds of them. From a daffodil yellow all the way down through corals and oranges, a little bit of green in there, down to a flaming hot pink. I tried to integrate that ombre through each strip and then patchworked them all together. It was over 200 strips, and each strip may have had several different fabrics in it. I made the whole piece out of this textile and stitched the Dangerous Female logo on the front. I was so excited about it because it's just like a sunset in a dress. I wanted to capture the warmth and ferocity of women. It was an exciting piece to make, and it took so long, and then they auctioned it off.

Having built such an impressive audience, what advice do you have for others with a hobby interested in either monetizing it or just bringing it to a bigger audience?

I think sharing your work in a way that feels authentic to you is awesome, if you can not worry too much about what other people are doing. It's always going to be a unique point of view. That's valuable. I think it's easy to get pretty serious about stuff when you monetize your hobbies. But I would encourage others, if they can afford to keep some play in their work, not take it too seriously. I know that's a bit of a privilege because it’s people's careers and their money. But I think that helps in terms of not getting too burned out or overwhelmed with the pressure of building an audience online, which is basically completely out of all of our control. You put it out into the internet, and it's just up to the internet and other people. So keep it fun and keep it as chill as you can, take the pressure off as much as you can.